Climate: is there any hope?

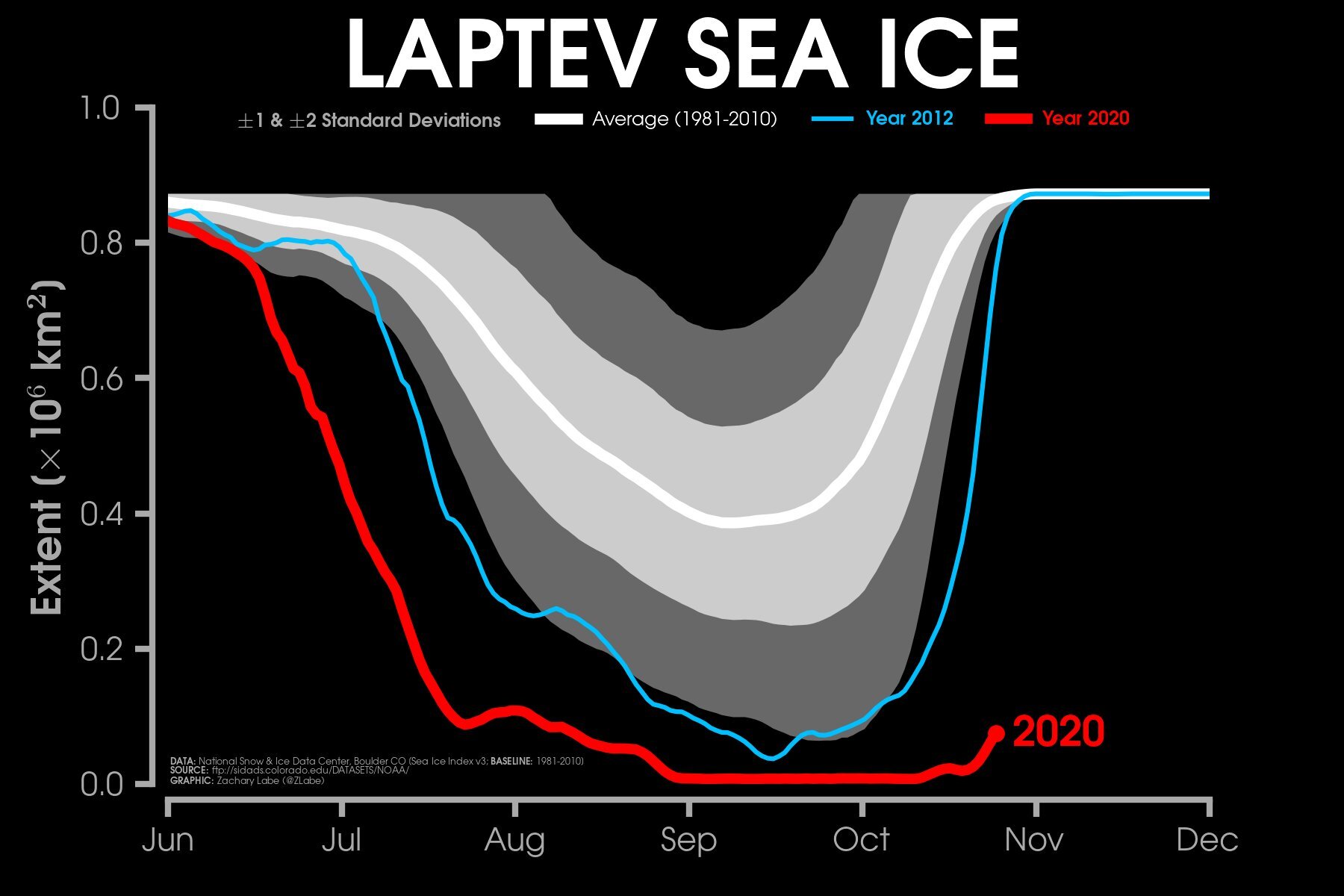

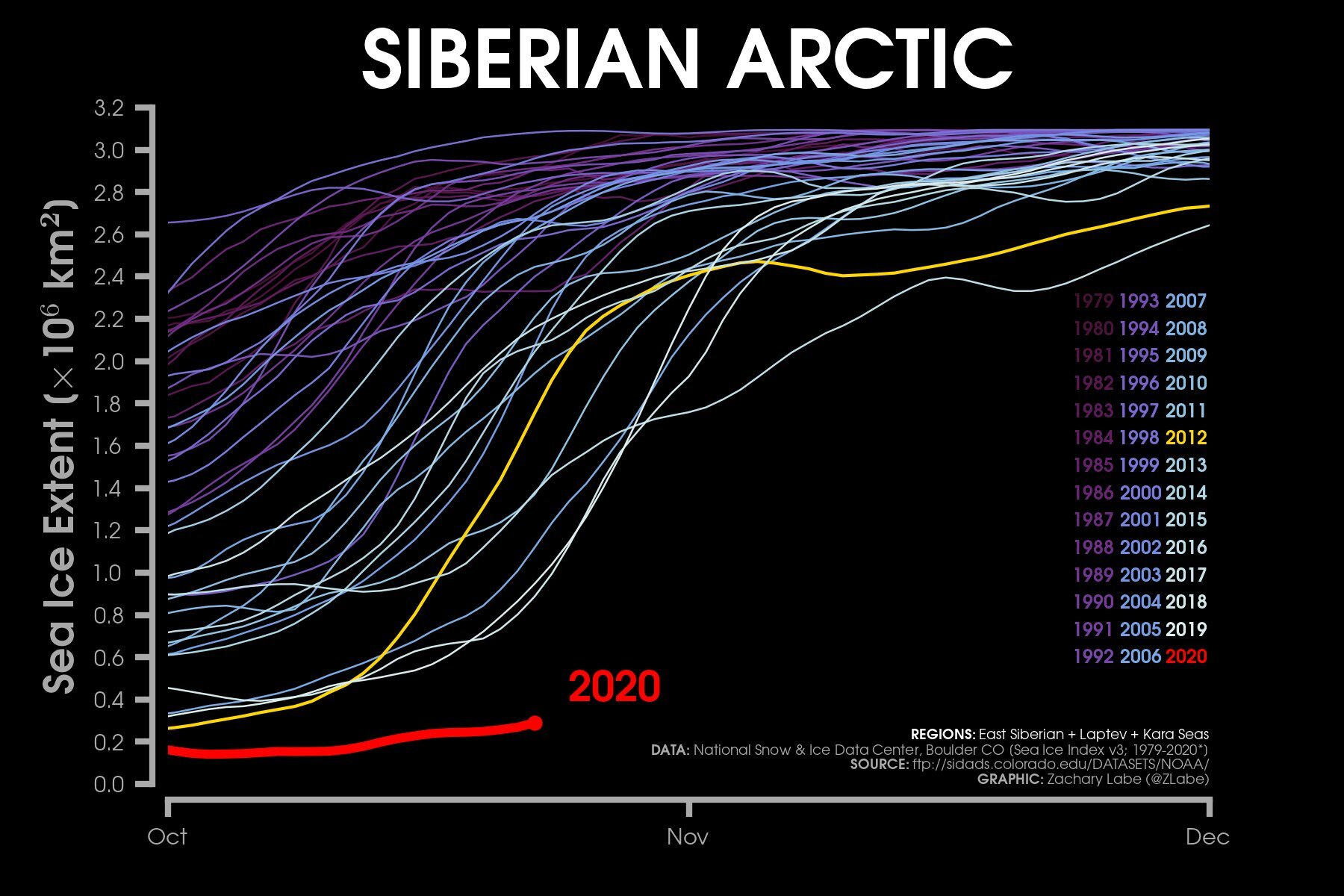

Image Source: Zachary Labe - Siberian Arctic and Laptev Sea Ice

It’s been a bad year for the climate. Raging fires in Australia and California, possibly the warmest June on record, and parts of the Arctic have not even begun to refreeze. Our hopes of mitigating climate change are gradually melting away.

And with the virus, few seem to truly care.

What can be done? The cost of renewables may be plummeting: the cost of solar power has fallen by around 90 percent since 2009, while the cost of wind power fell by around 38 percent. But it will take a long time to wean the world off fossil fuels: even under optimistic scenarios of renewable energy deployment, fossils fuels could still account for around 50 percent of the overall energy supply in 2050.

Moreover, we will be left with a carbon hangover long after the fossil fuel binge comes to an end. According to a highly-cited study, 20 to 40 percent of emitted CO2 could remain in the atmosphere for twenty centuries, enough to substantially impact the climate for thousands of years. The precedent for this is the Paleocene-Eocene thermal maximum 55 million years ago, when there was a sharp injection of carbon into the atmosphere and ocean. According to some estimates, it took the Earth around 150,000 years to recover.

As our atmosphere drenches with CO2, the hopes of many will be drowned out by the resulting political and economic chaos. Sweltering temperatures will dent economic productivity, heatwaves will lead to water shortages if not war, and increasingly powerful floods and hurricanes will ravage increasingly decrepit infrastructure.

In the face of such threats, the meagre changes proposed to date are woefully inadequate. Big change is needed: as a collective, we need to reduce consumption, something which has become an unthinking habit. But humanity is a complex system, comprised of billions of entrenched patterns of behaviour. Changing just one pattern or habit is hard — doing so for hundreds of millions of people is perhaps impossible.

But it would be remiss of us to not conceive of a way to change individual behavior. As a society, it is a capability we need to develop; even of it is too late to stop climate change, there are other threats — both known and unknown — on the horizon to which we will need to adapt. So how do we change a complex system?

To answer this question, it is useful to draw on the framework developed by Donella Meadows in Leverage Points: Places to Intervene in a System. A leverage point is a place in a system where a small change in one thing leads to a big change in outcomes. In order of increasing effectiveness, some of the points she described are:

12. Constants, parameters, numbers (such as subsidies, taxes, standards).

10. The structure of material stocks and flows (such as transport networks, population age structures).

5. The rules of the system (such as incentives, punishments, constraints).

4. The power to add, change, evolve, or self-organize system structure.

3. The goals of the system.

2. The mindset or paradigm out of which the system — its goals, structure, rules, delays, parameters — arises.

1. The power to transcend paradigms.

Strikingly, most governments attempt to deal with the problem of climate change by adjusting number 12 e.g. subsidies for renewable energy, and taxes on carbon and fuels. As we saw in the case of the French fuel tax, this often fails in the face of popular discontent. Number 10 (the structure of flows) is also frequently adjusted, for example by introducing more cycling paths, pedestrianising streets, and prioritising public over private transport.

But our current system finds it difficult to adjust the most powerful leverage points, which is probably necessary to enact deep systemic change. Why is that? First, let’s take point 4 and 5: the power to add, change, evolve, or self-organize system structure. We don’t see much of this in the public sector. Our institutions were mostly developed in the 1800s, and have not changed too much since then. IT has been added to the mix, but we in the West still largely have parliaments elected on a regional basis, and a civil service that reproduces itself through a hierarchical, top-down selection process. I may be overly cynical here, but those who have rose to the top of a hierarchy are winning the game; they won’t want to change the rules. And even if we do see innovation in private sector organisational forms, that permeates very slowly into the public sector. If the lever even exists, it’s stiff and rusty.

Point 3 refers to the goals of the system. In our current system, the goal of the collective is nothing more than the sum of the goals of the individual. But without a collective narrative, many tend to find status and meaning by pursuing professional success. Such success is then advertised by conspicuous consumption of goods and travel experiences, the acquisition of which strains the resources of the planet. Whereas in the past many prayed for entry into heaven, today many pray for entry into the upper middle class and the lifestyle it affords. Ironically, this striving for individual salvation is leading to collective damnation.

The goal of the system is the result of the mindset of the system, which is Point 2. On both the political left and right, this is usually an individualist mindset in the sense which often emphasises the story of the individual without relating it to any collective story. It is not clear if this mindset has the ability to change itself, which could be interpreted as the most powerful leverage point.

“One thing about which fish know exactly nothing is water, since they have no anti-environment which would enable them to perceive the element they live in.”

If few know how to lever the highest points, it may be because it is quite difficult to understand and step out of our mindset — much like Marshall McLuhan’s point about fish quoted above. Understanding our mindset thus requires another to serve as a contrast. Is there a worldview which could serve as an upgrade of the liberalism shared across the political centre? In this sense I would contrast it with Metasophism, the core imperative of which is that we should build a creative and cohesive society in the hope that one day we may unravel the mystery of existence. This is a broad mission which can only be fulfilled as a collective, countering the idea of purely individual and materialistic success.

But the collective should not dominate, and the individual must be free to choose their own way of contributing to the Imperative. This involves allowing people to form their own stories and groups — without requiring the consent or resources of those older or more senior to them. By preventing the rise of a rigid hierarchy, it therefore has a higher capability on Point 4 as well.

A worldview such as this is necessary to deflate the consumptive craze of modern society — and therefore address the issue of climate change. But the best feature of this ideology is that because the fulfilment of the mission requires the survival of humanity, people might start to care about the long-term. And then, finally, there might be hope of solving the problem of climate change after all.

————————————————————————————

If you liked this article, you might also be interested in my longer essay on the environment and climate here.

Metasophism is a work in progress — to follow its development, subscribe for updates here!